Route Tips & Commentary

Alaska is a difficult place to do a long hike. There are few manmade trails or tracks of any notable distance. The brush is often prohibitively thick. Glaciated mountain ranges, swift rivers, and expansive bog lands make many areas impassable during the summer months. And it’s very easy to leave the convenient reach of civilization, which a rookie Alaskan traveler might want to avoid until a certain confidence and competence is gained.

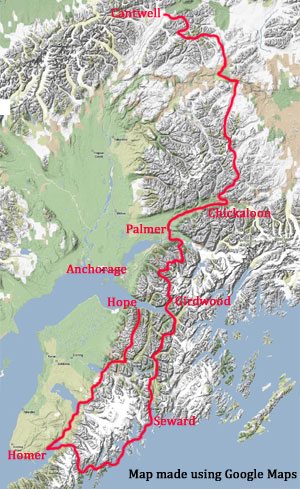

After months of staring at maps of Alaska, I finally put together a 700-mile route that I thought was worthy. It was a conglomeration of routes that I knew had been done before or that looked doable on the maps. There were basically six legs:

- Kenai Mountains: Hope to Homer

- Kenai Fjords: Homer to Seward

- Eastern Kenai Peninsula: Seward to Girdwood

- Western Chugach Range: Girdwood to Palmer

- Matanuska Valley: Palmer to Chickaloon

- Talkeetna Mountains: Chickaloon to Cantwell

Of the six legs, I felt that four were significant and distinct enough to be stand-alone hikes, hence the name of the whole trip, Four-Range. The Eastern Kenai and Matauska Valley sections were really just connections between the good stuff.

Route Description

Leg 1: Kenai Mountains—Hope to Homer

This is the original Alaska Mountain Wilderness Classic route. It starts in the small village of Hope, on the south shore of Turnagain Arm, and follows the 40-mile Resurrection Trail to Cooper Landing on the Kenai River. From here, racers used to follow the Russian Lakes Trail and bushwhack through the Hills of Confusion to the Skilak River Flats. But things have changed since the early 1980’s—packraft design has improved immensely and the Kenai Peninsula has been hammered by spruce bark beetles, making many bushwhacks (including the Hills of Confusion and along the west shore of Skilak Lake) even more arduous than they were before. Today, the most efficient route is to float down the Kenai River to Skilak Lake; I was uncomfortable floating the Class III canyon above the lake alone so I followed the trail on the river’s east side for that section. Skilak Lake is known for wicked winds but it was glassy when I floated into it, and the paddle to Cottonwood Creek Trailhead was easy and pleasant. The frequently traveled Cottonwood Creek Trail took me up into alpine and I made my way over towards Benjamin Creek. Apparently there are good game trails that run parallel to Benjamin Creek and along the Killey River; I made the mistake of staying high and trying to contour above the brush, which was effective until I needed to cross the Killey River Valley without the assistance of game trails—it was treacherous, awful, and slow. There is excellent tundra on the bench between the Killey River and Indian Creek. A maintained use trail drops west from the southwesternmost alpine knoll to Lake Emma; pick up the trail on the knoll’s north side. There is a free, public cabin at Lake Emma. A good trail leads from the cabin to the shores of Lake Tustumena near a private cabin.

The paddle across Lake Tustumena could be hindered by wind whipping down the glacier. If so, no problem—it’s possible to follow the shoreline most of the way to Devil’s Bay. The forested, rocky bluffs in the middle of the glacial flats may offer enough wind protection to paddle around, avoiding a tough bushwhack through that section. The primary outlet river of Tustumena Glacier will probably be impassable during the warmer months—I blew up my raft there, paddled across the outlet, and then ferried southeast into a stiff headwind, with my ultimate direction being due south towards Devil’s Bay.

The four miles between Lake Tustumena and the Fox River feature the most difficult bushwhacking of this leg and of the entire Four-Range trip. Spruce bark beetles killed most of the spruce in this area and many of the trees have been blown down, making a bad situation worse: the vegetation has always been thick here, but now it’s even thicker because the canopy has opened up and the forest floor is littered with sharp spruce snags. It took me 6 hours to get through this section and my rain pants were torn in at least four places.

It was an easy Class I float to Kachemak Bay. I had to be cautious of wood in the river; there are a lot of beetle-killed spruce trees lining the banks. I only had to portage around one section, where the river had carved a new channel through a forest of cottonwood trees. At high tide it is possible to float the Fox River all the way into Kachemak; at low tide the river was too braided and shallow. I should have taken out just before the start of the tidal flats and headed west to the ATV track, but instead I tried to reach the bay at low tide and got stuck, making for a sloppy walk across the muddy flats.

To reach Homer I hiked along the fast shale shoreline to McNeil Canyon, where I followed a private farm road through the historic Kilcher homestead. My maps did not indicate this was a private road so I stopped at one of the homes in order to apologize and ask for permission to cross their land, which they were quick to give me—I think they are more concerned with ATV use. I hitched into Homer as soon as I got out to East Road. A faster way into Homer than McNeil Canyon is the well travelled road just southwest of the Russian Village at the bottom of Swift Creek. It cuts steeply up the bluffs towards East Road.

Leg 2: Kenai Fjords—Homer to Seward

This leg was inspired by a trip done by Erin McKittrick and Brentwood Higman (“Erin & Hig”) in 2004. The basic approach is: paddle across a fjord, hike across a peninsula, hope for good weather, and pray that all the passes go. This leg had the greatest consequences in the event of failure: I was separated from safety by frigid glacial fjords, rugged peninsulas, and a huge icefield. Thankfully I managed to get through this section safely and without incident, though it was certainly difficult and stressful.

From Homer I hitched back out to the Kilcher property and descended back down to Kachemak Bay. I paddled across calm waters and reached Bear Cove at 1 AM; I bedded down on the front porch of a private cabin to avoid the morning dew. I hiked over to Battle Creek and picked up the wide, unmapped gravel road that leads up to Bradley Lake and the hydroelectric dam.

It was too windy to paddle across Bradley Lake so I climbed up to the glacier-scoured, tundra-covered granite domes on the lake’s north side. It was pleasant but difficult hiking—there is a lot of unavoidable up and down through here. I eventually descended to the lake’s eastern shore, which is about two miles up-valley of its natural shoreline, near the western tip of the ridge that separates the Kachemak and Nuka Glaciers. I contoured above the brush on the north slope of the Nuka Valley for a while, but it was very slow so I descended into the valley and picked up an old ‘dozer track that connects several research stations in the valley. The ‘dozer track ends at the last research station just east of Nuka Glacier. From there I followed the braided creek a short ways further until reaching beautiful tundra, which extended to just beyond the large lake perched on a bench about 1.5 miles north of the forested Nuka Flats.

I descended steeply down some house-sized, alder-covered boulders to where the first Exit Glacier lookalike glacier enters. I blew up my raft here and floated down for less than a mile before hurriedly taking out when the creek dropped into a Class III rock garden, Class IV chute, and Class V waterfall. I bushwhacked south through nasty alder and devil’s club to the graveled outlet of the next Exit Glacier lookalike and followed this down to the main river, where I put in again and floated all the way to Beauty Bay, save for a few snag-induced portages.

There is a nice, infrequently used Park Service cabin about 1.5 miles south of Pilot Harbor. To reach the pass between Pilot Harbor and James Lagoon I followed game trails into a snow-filled gorge/avalanche chute, which I was able to follow for most of the way to the bowl beneath the pass. On the opposite side I dropped about 1,000 vertical feet down another avalanche chute to a small flat area located just above a high waterfall, which I dropped steeply around on its north side through forest and alder.

I paddled across East Arm to Desire Lake (the unnamed lake north of Delight Lake), which is protected by a thick mile-wide alder forest and bog. I had relatively decent success paralleling the outlet creek—there is lots of bear activity along it because of the salmon runs. (“Relative” to bushwhacking through thick alder…) I paddled across Desire Lake and followed the gravelly creek to the base of a cascading waterfall, which I stupidly (but successfully) climbed up on slippery rocks, loose talus, and steep snowfields. I would probably recommend going southeast and seeing if it’s possible to contour around into the bowl below the pass—my route was really unsafe. From the pass, there were scree/talus fields and good bear trails that quickly got me to Taroka Arm.

There are no non-technical options over the next peninsula, so I paddled almost 20 miles to Northwestern Lagoon. This would be a very difficult paddle in stormy seas—there is no protection from whatever is happening in the Gulf of Alaska. The Harris Peninsula crossing was perhaps the easiest and most pleasant of this leg. I followed bear trails along the river to the northwest corner of Section 8 before climbing 500′ southeast to granite slabs and alpine. I continued climbing to the large lake at 1,000′, which I hiked around on sloping snowfields on its north and northeast sides. There is a small tarn above the lake and the pass is just beyond. I descended on solid talus and boulders all the way to McMullen Cove. I paddled a half-mile northeast and camped on the forested beach because there are no good campsites at the bottom of the descent, just rocky shoreline.

The next morning I paddled across Aialik Bay and climbed up the 500’ high pass in the northeast corner of Bear Cove. I was planning to cross at Coleman Bay but this pass was much easier and the seas were favorable. Bear trails led up through old growth forest adjacent to an avalanche chute before dropping into the chute and continuing up to the pass. On the north side there was a steep, loose rock chute that was okay once I got into it. A better way down would have been just to the east, on more moderate slopes.

There is a terminal lake at the end of Bear Glacier now. It is worthwhile pulling ashore and paddling amongst the icebergs. The outlet river of the glacier and the lake is at the far eastern edge of the beach, just before Callisto Head. I picked up the Caines Head Trail on the south edge of Caines Head, near the outlet of an unnamed creek that flows due south through Section 22. Caines Head Trail is not passable at high tide between Derby Cove and Lowell Point so check your tide charts in order to avoid having your cheeseburger feast in Seward delayed.

Leg 3: Western Kenai—Seward to Girdwood

I followed the bike path along the Seward Highway out of town until turning off for the Lost Lakes Trailhead, which is about a mile off the highway; the signage is good. Lost Lakes is an easy and beautiful trail, as is Primrose. I reached Primrose late in the evening, paddled across the lake with the help of a north-blowing wind, and walked along the highway to Moose Pass, where there is a very small grocery store, a motel, and a restaurant. A few miles beyond I jumped on the Johnson Pass Trail, which is another really nice trail. I broke off shortly after it crosses to the north side of Bench Creek in the Center Creek Valley. I managed to pick up a flagged route and excellent bear trail up Center Creek until I reached a meadow of thick willows, where the flagging tape and bear trail came to a sudden stop. I slogged through dense dwarf spruce for a while before I found some meadows that I could link up to Center Creek Pass. I descended steeply down to the Placer River from the south pass (not the one with the tarn). It took about an hour: at first I was in seasonal vegetation, then in open old growth spruce, then finally in alder. There is talk of making this route part of a “Whistle Stop” trail system, but thus far it’s just talk and some flagging tape.

The Placer River was an easy Class I float to the Seward Highway. I caught an outgoing tide and a strong west wind blowing from Portage Pass and quickly floated down Turnagain Arm. It was critical that I knew where the main channel was in order to avoid getting hung up on the dangerous mud flats. I took out at Notch Point, about 2 miles east-southeast of Girdwood, and walked into town.

Leg 4: Western Chugach—Girdwood to Palmer

I resupplied in Girdwood, hiked over Crow Pass, forded the Eagle River, and left the Crow Pass Trail just after Dishwater Creek in Section 23. There is a use trail that climbs steeply up to the toe of the moraine above; I picked it up by following Dishwater Creek up a short ways before cutting west through the forest to a trickling stream, which the use trail paralleled. I continued climbing to the bench at 3,700′ and then descended directly into the drainage just to the north—I was not happy about losing some elevation but it’s not really possible to contour down off the ridge into the drainage.

My recommended way over Bombardment Pass is by climbing up the north valley wall on tundra slopes adjacent to the rock bands. Once above the rock bands, contour over to the pass. Do not try to climb through the rock bands below the pass like I did—it’s steep, loose, and scary. To reach Rumble Pass I contoured around onto the glacier around the corner—there was no need to go down and then climb up again. I picked up an excellent use/goat trail southeast of Point 5,530′ and followed it about 1.5 miles to the lip of this hanging valley above Peters Creek before descending excellent tundra to the valley bottom.

I hiked down the braids of Peters Creek or walked through tundra on the west side when the creek channeled up. After almost 3 miles I began hiking northeast towards the creek that drains the valley below Thunderbird Peak. I picked up a good game trail along the way and followed it down-valley to the creek. In order to get out of the willowy brush as quickly as possible I climbed up towards Peak 5,360′, contouring northeast as I neared the top in order to avoid unnecessary elevation gain, then followed goat trails along this spectacular ridgeline all the way to Thunderbird Peak.

My original plan was to descend the ridgeline that passes through the southern parts of Sections 3, 2, and 1. But I was lured by the expansive scree slopes east-southeast of Thunderbird Peak—I scree-skied 2,000 vertical feet down in a little under a mile and then continued down tundra into the creek bed running almost due north in the eastern part of Section 11. Figuring that there might be a game trail running parallel to this creek, I jumped up on the rise of land just south of the creek and found a great bear trail that soon entered the alder. To my surprise I also found flagging tape along this bear trail, and I followed it for quite a ways down until I lost it near the creek in some alder and devil’s club. I gave up on the trail at this point, thinking I was close enough to the Eklutna River that it wasn’t worth the time in re-finding it. That was a mistake—I still had quite a while to go, and I had to beat through alder and devil’s club, and then bettle-killed spruce, before reaching the river.

The Bold Ridge Trail offers an easy (by Chugach standards) way to reach alpine—it’s an old jeep track that is well maintained today by regular hiker traffic. When I reached the end of the trail, I followed a use trail across the valley and climbed the tundra-covered ridge to the northeast. I dropped into the next drainage near the 4-corner junction of Sections 17, 16, 20, and 21. I then climbed east and north to a saddle northeast of Peak 5,430′.

From this saddle it was a superb ridgewalk to the Pioneer Ridge Trail. There was a lot of climbing and descending along the ridge but most of it is really friendly terrain; goat trails abound. Pioneer Ridge Trail begins 2 miles southeast of Pioneer Peak, at Peak 5,330′. This glorified use trail descends rapidly to the Knik Road—5,200 vertical feet in about 4.5 miles.

I walked the Knik Road to the Old Glenn Highway, which I took into Palmer.

Leg 5: Matanuska Valley—Palmer to Chickaloon

This was the worst of the six legs and I would never recommend hiking it unless you had to. It’s entirely on roads, mostly the Glenn Highway, which receives moderate traffic. I also had to contend with “hot” temperatures and cloudless skies; and my views of the beautiful Matanuska Valley were mostly ruined by thick smoke from wildfires all over the state.

From Palmer I hiked to the local NOLS branch and spent the night. The next morning I hiked to Sutton and picked up my maildrop at the Post Office; the postmaster there has a huge, awesome personality. From Sutton I was planning to just hike a few more miles on the Glenn to the Kings River, where I thought I would be able to follow ATV tracks (named “Chickaloon Trail” and “Chickaloon Knik Nelchina Trail”) all the way to Boulder Creek. Unfortunately the trail from Chickaloon to Boulder Creek no longer exists, so I had to hike all the way to the Puritan Creek Trailhead at MM 91.

Leg 6: Talkeetna Mountains—Chickaloon to Cantwell

This was a magical section, probably my most favorite of the trip. I hiked on hard tundra through beautiful mountain terrain for most of the way; I floated 14 miles down the famed Susitna River; I went 6 days without seeing anybody, 5 days without seeing a manmade track, and 4 days without seeing a human footprint; and I saw caribou almost every day and followed their trails extensively. I would highly recommend this leg as a stand-alone backpacking trip.

From the Puritan Creek Trailhead I followed ATV tracks into the Boulder Creek Valley and up towards Chitna Pass. I often could follow a good ATV track on the creek’s northwest side. I climbed up to the pass between Boulder Creek and Glass Creek and unnecessarily climbed to a higher pass with a small tarn in order to have a cleaner approach to the confluence with Glass and Caribou Creek. Many of the creeks in this part of the Talkeetna’s are lined with vertical walls and it looked as if the confluence was open in this regard, whereas Glass was clearly well protected. In retrospect, I should have just contoured northwest from the pass and dropped down above where the creek begins to gorge up, then hiked up and over the bench into Caribou Creek. There is an excellent game trail along Caribou Creek on its southwest side.

I climbed a 5,100′ pass near the headwaters of Caribou Creek in order to enter the Oshetna River drainage. There is a small but sound outfitter cabin 5.5 miles down-valley in the northeast corner of Section 21, southwest of Point 4,605′. I saw thousands of caribou in this area. The walking is pleasant; the tundra is a touch thick with grass. I contoured above brush into Nowhere Creek and climbed a tundra-covered 6,150′ pass in Section 12. The backside of the pass into the Black River valley was acceptably steep and loose with sand and gravel—this area was covered by glaciers not too long ago and vegetation has yet to move in.

I forded the braided Black River and followed it downstream into Section 25, where I crossed two tributaries just above their confluence. A Super Cub plane crashed on the bench just south of this confluence and the fuselage is still there. From the confluence I climbed up to the benches above, towards the lakes. I heard it is possible to cross the pass located west of these lakes on steep scree, but I decided to continue north into Section 7 so that I could take a high route north along the flat-topped ridges 11 miles before reaching Kosina Creek. Incoming thunderstorms ixnayed that idea, but it still worked out well: the pass into Kosina Creek was easy, and it’s clearly preferred by the caribou, which have made numerous use trails over it. Note that it is also possible to climb from the Black River up to Section 7 on good tundra slopes—this may be a shorter route and have less climbing.

I was hoping to float Kosina Creek all the way to the Susitna River but this proved not possible. Above 3,500′ there was not quite enough water—maybe earlier in the season there would be. Below 3,500′ there was enough water but the creek often became a shallow 200′ wide rock garden that required portaging. With good game trails running along both sides of the creek, and/or with good tundra on either side, I decided that it was more efficient to hike downstream than to paddle-portage-paddle-portage down. Below the confluence of Terrace Creek the vegetation became frustratingly brushy and the creek looked regularly floatable, so I put in one last time and floated to just above the confluence with Tsisi Creek. Here, the volume of Kosina Creek almost doubles, and it enters a Class III canyon, so I hiked down to the confluence with Gilbert Creek, hoping to spend the night in a cabin only to find that the cabin no longer exists.

From Gilbert Creek, Kosina Creek is a Class II/III creek—fun and splashy, with some shallow rock gardens where getting out of the boat is necessary. There are good game trails for much of the way down parallel to the creek too.

The clear Kosina Creek feeds into the opaque waters of the glacier-fed Susitna River. I floated the river about 14 miles down to Deadman Creek—it was pleasant Class I and I hung my feet outside my boat to dry in the warm sun. Just below Deadman there is a constriction that results in a good wave train; and many miles beyond that the river enters the Class V Devil’s Canyon.

My thinking in getting out at Deadman Creek was that there probably would be game trails along the creek in order to help get me back up to the magical 4,000′ contour, where brush totally gives way to joyous tundra. My thinking was quickly validated: I picked up a game trail immediately on the west side of Deadman that ran up along the edge of the canyon rim above the creek. I followed remarkably good moose and bear trails through dense willows and eventually dropped down to the creek in Section 13. I slogged through willows along the east bank of Deadman on an intermittent bear trail until Section 35, where I picked up a great tundra bench that ran parallel to the creek on its south side.

The tundra bench began getting brushy again and I decided at this point to ford the creek and cut straight up the green-shaded south-facing slope on the north side of Deadman, which was not forested at all but rather a mixture of willows and meadows. I stitched together meadows and game trails and reached good tundra just above 3,500′.

I had extra time and food, and the bugs were annoying, so I climbed up Peak 5040′ and Peak 5510′ and descended a steep glacial bowl into Section 23. I hiked north over a pass, dropped into the next drainage, climbed north-northwest to the next pass, descended slightly, and then climbed to a final broad pass at 4,200’—all on awesome tundra.

From this broad pass I descended a tributary of Tsusena Creek. It got brushy towards the bottom but there were good game trails. I crossed Tsusena and hiked up the tributary on the opposite side, then climbed a pass to the north in order to get into the East Fork of the Chulitna River. The scenery was spectacular. After 6-7 miles I turned east towards the Jack River and Caribou Lakes. I picked up a great game/use trail on the west side of the Jack River Valley that presumably goes to the shelter on Caribou Lakes. I peeled off and wasted time by staying high on the north side of the valley in order to stay out of the Jack River canyon—this was bad advice I received. Instead, I should have just dropped into the canyon and hiked through it—it would have been totally doable, though perhaps not during peak melt.

I picked up the remnants of an ATV track about halfway to Soule Creek; the track became very obvious north of this confluence. Jack River was floatable from Soule but I did not put in until the East Fork entered, the next morning, in order to avoid getting wet just before camping. From the East Fork, the Jack River was a splashy Class II creek. I was concerned about the canyon just before it exits from the mountains, but the character of the creek did not significantly change. North of the canyon the river moves through gravel braids all the way to the Parks Highway; it may become too shallow to easily run late in the year.