Campsite selection is a critical backpacking skill, nearly on par with navigation and fire-starting. In this four-post series and in the video embedded above, I share what I know.

- Part 1: Importance, regulations, LNT considerations, planning, zones and spots

- Part 2: Ideal features of camping zones

- Part 3: Ideal features of camping spots, and tradeoff balancing

- Part 4: Four examples of classically bad camps

Campsites are not created equal. Where possible, I seek out locations that are relatively warm, dry, private, aesthetic, and free of bugs, rodents, and bears — “five-star campsites,” I call them. A high quality campsite makes a difference:

- It is more conducive to a night of quality sleep, and

- It enhances my backcountry experience.

Sadly, I see many backpackers who lazily choose their campsites and/or who cannot differentiate good campsites from bad. They select sites that are cold, prone to pooling rainwater, at risk of heavy condensation, intruded upon by other campers, and home to copious mosquitoes and four-legged scavengers.

Some backpackers try to offset poor campsites with their equipment. They sleep in double-wall tents, so that they are protected from condensation by the inner body. They cozy up in synthetic-insulated sleeping bags, so their warmth is not as compromised by moisture. And they carry plush and excessively warm sleeping pads, so that they can sleep comfortably on any surface.

Personally, I prefer to simply find better camps.

An excellent camp near West Virginia’s Spruce Knob. Warm, well protected, insect-free, cushioned, and flat and level.

Regulations and LNT

Camping wherever I please is not permitted on all public lands. Especially in high-use areas like Yellowstone National Park, many land managers concentrate and cap backcountry use by requiring that backpackers stay in designated campsites.

While I’ve never found a designated site that earns a five-star ranking, I try to make the best of it. There is a range of quality, both between and within camping areas. For example, in Rocky Mountain National Park, Sandbeach Lake is a better site than Gray Jay; and at Caribou Lake in the Indian Peaks Wilderness, site #6 is better than site #2. Among what is available and compatible with my itinerary, I take my pick of the litter.

When at-large camping is permitted, I prefer to use virgin campsites (or very lightly used ones) and stay away from popular areas. But this is not always appropriate, or consistent with Leave No Trace (LNT) guidelines. Specifically, when I’m backpacking with a group or when I’m planning an extended camp, I try to limit my impact by using established sites (if available), rather than creating new ones.

Backpackers must stay in designated campsites in Rocky Mountain National Park. It’s the worst aspect of backpacking there. The camps are hard and dusty, at risk of pooling rainwater, and home to rodents.

Planning

One of my evening in-camp rituals is formulating a plan — with a varying level of specificity — for the following day, and perhaps a day or two beyond as well. When I leave camp in the morning, normally I already have identified several areas where I may sleep that night.

These prospects are based on expected mileage (or vertical, for routes with extreme up and down) and on what seems most promising. My plans are informed by my datasheets, topographic maps, guidebooks, and/or what I have learned from other backpackers.

Detailed maps are critical in finding good campsites. In the US, I recommend the USGS 7.5-minute series, as shown in the screenshot below. (Read more: Essential backpacking topo maps.) They depict the topographic relief and the vegetation with more precision than small-scaled recreation maps like the National Geographic Trails Illustrated series.

As the day progresses, my options narrow. For example, I project my ETA at Prospect A to be too early, and at Prospect C too late. But I’m on perfect pace for Prospect B.

Datasheets are useful in identifying prospective campsites. I consider how far I want to walk and approximately where that would put me. Then I look at my topographic maps.

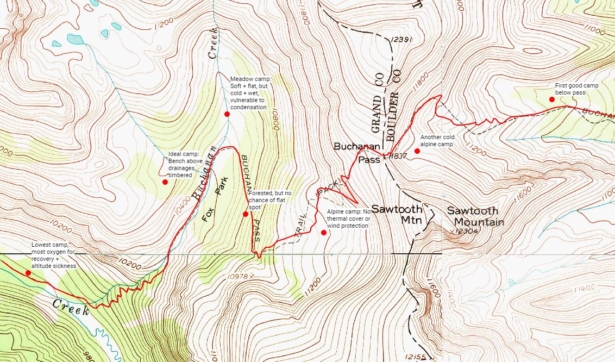

Based on expected mileage for the day, I examine my topo maps for prospective camping zones, and weigh their pros and cons. Zoom in to read my notes; assume that I’m hiking left to right, along the red line. As the day progresses, I narrow down the options.

Zone- and spot-level selection, and shelter types

It’s useful to evaluate campsites on two levels: zone and spot. (I have referred to them as macro and micro, too.)

- A camping zone is a general area, like a ridge or a canyon.

- A spot is the exact location where I pitch my shelter.

The respective quality of zones and spots is important, but ultimately a quality spot is more important than a quality zone. I can still sleep decently on a breezy ridge, but not in an inch-deep puddle.

Regardless of whether I am sleeping on the ground (under a tent or tarp) or between two trees (in a hammock), the characteristics of a high quality zone are the same. For example, in both cases I want to avoid the bottom of drainages, where the air is relatively cold and humid.

But my perception of a high quality spot changes with my shelter. For example, as a ground sleeper I must find a root-free footprint, whereas in a hammock I can hang over a briar patch if I care to.

1) I primarily camo in Alpine areas of the High Sierra. Tree cover that provides any thermal benefit is rarely an option. Nevertheless, I’m curious how of a temperature difference were talking about.

2) How far from the valley floor do I need to get away from the sinking cold air? Often the only flat spot is near a creek or drainage, or up on an exposed ridge in the wind. What is colder, wind chill or the cold damp air that flows downhill?

3) I am usually looking for a site with the following considerations in mind (in order) proximity to water, flat spot w wind protection, aesthetics and felt sense of rightness, early morning sun exposure, vistas. Those are not mentioned in your post…

4) wjats that grey shelter with the single pole. I’m still trying to figure out what tarptent to get to replacey big agnes fly creek, now that I started using trekking poles

1. I’ve spent a lot of time in the High Sierra, often in terrain typified by the Sierra High Route and Kings Canyon High Basin Route, and rarely have had to camp in the alpine. Pull up a couple of miles earlier, or go a couple of miles more, and you’ll have some thermal cover. On calm and cloudless nights, which are common in the High Sierra, thermal cover makes a big difference, probably 10 degrees, maybe 15. In the High Sierra I’ve found that it often makes the difference between having condensation and not.

2. The recommended distance depends on the shape of the valley and the watershed size. If it’s a broad valley and a small watershed, not far. If it’s a tight canyon and a big watershed, then further. The High Sierra primarily consists of ridges and valleys, but there are many benches between those two features. Below is a map of Cold Canyon, which is in Yosemite and on the PCT.

3. In Part 2 of this series I will discuss campsite characteristics. Regarding proximity to water, I think it’s a net negative: cold air, high humidity, insects, and people.

4. That is the SMD SoloMid. I think there are better shelters out there, from SMD and other manufacturers. While it has a decent-sized footprint, the usability of the perimeter space is limited due to the wall angles. Ventilation is limited in a rainstorm, when you need ventilation the most. And personally I like double-wall shelters because they are modular and thus more versatile.

Andrew,

This is all good stuff, and thank you for the reply.

– In your post you seemed to suggest that double wall shelters were unecessay and cheating given proper campsite selection, but in your reply to my comment you say you prefer them. I’m a little confused. I think I am going to go with a tarptent notch. What else do you recommend I look at. It seems good for me because it’s not too expensive, and lighter than your High Route tent. I’d

– The map with the contrasting campsights is helpful. However, your comment about finding tree cover in the high sierra doesen’t square with my experience at all. This year I went on a number of trips. The first one was over July 4th, an off trail loop out of Twin Lakes into Hoover wilderness and Yosemite, with Benson Lake being the far side of the trip. The bug pressure was intense, and the main criteria for site selection was exposure and wind. Also being farther away from water, but not so far that I had too long of a walk. On the first night there wasn’t any option but to camp next to a lake as I bonked, and there was no tree cover on the more arid Eastern Slope. Night 2 I camped near a lake under tree cover. Night 3 I camped on a bench with complete exposure, quite a walk from the water, because I was getting eaten. Night 4 was at Benson, plenty of trees there and lucklily a strong breeze off the water. and night 5 I was deep off trail and tired, and in a narrow canyon with steep sides and no option but to camp in the middle of the valley near a stream. If I had continued it would have been a greuling off trail slog up into a higher valley without tree cover.

On a Loop out of Taboose Pass later in the sumer, the only night tree cover was an option was at Bench Lake. The rest of the trip I was too high. And it was cold! On the last night I was in Upper Basin, and I walked until dusk then spend quite some time trying to find a campsite not too far from the stream but with a nice flat spot, but the ground was covered with rocks and I finally gave up and woke up freezing due to the sinking cold air from the huge valley above.

Im not trying to argue, I genuinely want to learn and get better at this, but not all of what you are laying out is neatly integrating with my experience. Thanks for any further input (and I can wait for part 2)

Re double-wall tents, many prefer them so that they are protected from condensation (which collects on the interior of the fly) by the inner tent. In contrast, I prefer them because they are more versatile than single-wall tents. If I didn’t value the versatility, however, I’d go with a single-wall tent, and eliminate the condensation worry (mostly) through campsite selection.

Thermal cover is not always possible in the High Sierra. But if you execute your day well and have a decent understanding of what kind of vegetation you will find at certain elevations and slope aspects, you can find forested sites with good frequency. For example, two of the five nights in your July trip, it sounds like you camped where you got tired, instead of camping before that point. And the next time you visit Upper Basin, you’ll have more accurate expectations about campsite opportunities (or lack thereof).

Having been subjected to some needlessly dreadful selections in the past, I look forward to the rest of the series. I’ll be able to offer more pointed critiques when my group wants to make camp in a kangaroo rat infested grove, or a dry wash that’s the unofficial latrine area for the rest of the area.

Maybe I’ll just leave the rats & poo to the group and find a nearby Five-Star site for myself.

Also, my desire for solitude is leading me to more primitive trails and off-trail travel, so an article on how you incorporate datasheets into you trip planning would be welcome. My Ambit3 Peak arrives tomorrow, and I’m rethinking my trip planning with an eye for maximizing hiking time based on personal performance, not whatever looks ok in a guide book. The more gear weight I shed, the more I just want to move. Making camp with hours of daylight left feels silly anymore.

Andrew, did you create that data sheet by hand from a map, or is there some software assist on that?

In this particular case, it was manual. Draw a line on CalTopo between two points, and import the data into a spreadsheet. It’s been a while since I did a trip with an existing databook; but when I did, I would use that data and build onto it.

This was a great series (I read it backwards); thanks. I had a good time pulling up my notes and seeing how my planning and choices evolved, where they parallel yours, what good choices I’ve made by accident vs. by design, and what choices and compromises didn’t work out so well.

As usual, excellent information.

What it is the tent mfg and model of the tent pictured in the “An excellent camp near West Virginia’s Spruce Knob. Warm, well protected, insect-free, cushioned, and flat and level” photo?

Six Moon Designs Lunar Solo

Hi Andrew,

Thanks for all of your resources, I’m really enjoying reading through them as I get back into backpacking. I’m curious to know if there are any more resources that explain how to use topo maps to scout out potential campsites in a bit more detail? Thank you!

When looking at a topo map, consider:

* Slope angle (generally flatter = higher likelihood of campsites)

* Vegetation shading (timber = more thermal cover)

* Water ways (closer to water = more humid, pooling of cold air masses, more bugs during buggy seasons, and probably more people)

* Geology (e.g. erosion-resistant bedrock is more conducive to flat benches on otherwise angled slopes, whereas slopes consisting of dirt or sand are probably pitched at their angle of repose and have a uniform angle)

Some local knowledge is extremely helpful in looking for campsites on topo maps. In the High Sierra, for example, I know that I can find a campsite in virtually all timbered areas, because the understory is very light or non-existent. In Colorado, however, there’s more of an understory, especially in the fir/spruce zones (9-10k feet approximately), so I can’t assume quite as much; in the lodgepole forests, the floor is often littered with deadfall, due to the pine beetle epidemic. Finally, in the Appalachians the understory is much thicker and rarely consistent — sometimes it’ll be open deciduous or pine, and other times it looks like a rainforest.

Thanks Andrew for the detailed response. Much appreciated!

Andrew, a question that I could probably google and piece it together, but figured I’d ask.

-I’ve grown up in a country where there are no legal fires in the bush (national parks, regional parks etc). Campfires are things you have on private property.

-The West of the US has huge summer forest fire issues.

-How come I see pictures of campfires in US Nat Parks in the West, in the back country? Particularly in Yellow Stone on a 70mile back country route, the article I read showed camp fires.

-I’m guessing that maybe early spring, and winter, you’re maybe allowed them? But in the back country, you’d be using wood you find too. Surely the wood around the designated sites is all gone?

Thanks,

Each land management agency has its own set of fire regulations, and you need to familiarize yourself with them before entering. As an example, in Rocky Mountain National Park backcountry fires are only permitted in specific campsites with metal fire grates. Here, the park has decided that there is sufficient wood fuel. But even these campfire rings are subject to fire bans that can be implemented during the hottest/driest months after dry winters.

Just south of the park, in the same mountain range, is the Indian Peaks and James Peak Wilderness Areas. Fires are banned through James Peak and on the east side of the Continental Divide in the Indian Peaks, which is heavily used. On the lower-use west side of the Divide in IPWA, fires are permitted except in specific high-use areas (e.g. Crater Lake) and during fire bans.

My point is that the fire regulations are all over the place, sometimes legal and sometimes not. I would assume that the Yellowstone campfire was legal, and if not then the posters are idiots for sharing illegal activity with the world.

Great article but I do think it’s important to also consider the goal and style of the backpacking trip. For example in a more casual Sierra Club group trip I would look for a spot that can fit and house multiple shelters and apply all of the advice in this article as well as looking for something that might have a nice spot for the group to hangout in the evening and share food.

On a solo trip by myself however I often prioritise my view of the landscape more than anything – I love photography but even when I’m not taking photos waking up and looking directly out the door of my shelter at some epic alpenglow is one of the biggest reasons I go out in the first place. I still wouldn’t of course choose a spot where water will puddle, but I’d be much more tolerant to setting up on a windy ridge where I might end up getting smashed with a lot more precipitation than a more covered spot with natural wind blocks. Would be interested to see if you had any advice for campsite selection in spots not so ideal in terms of comfort and how to still maximise ease of setup and minimize potential problems.